The Fight for Human Rights in Three Revolutions

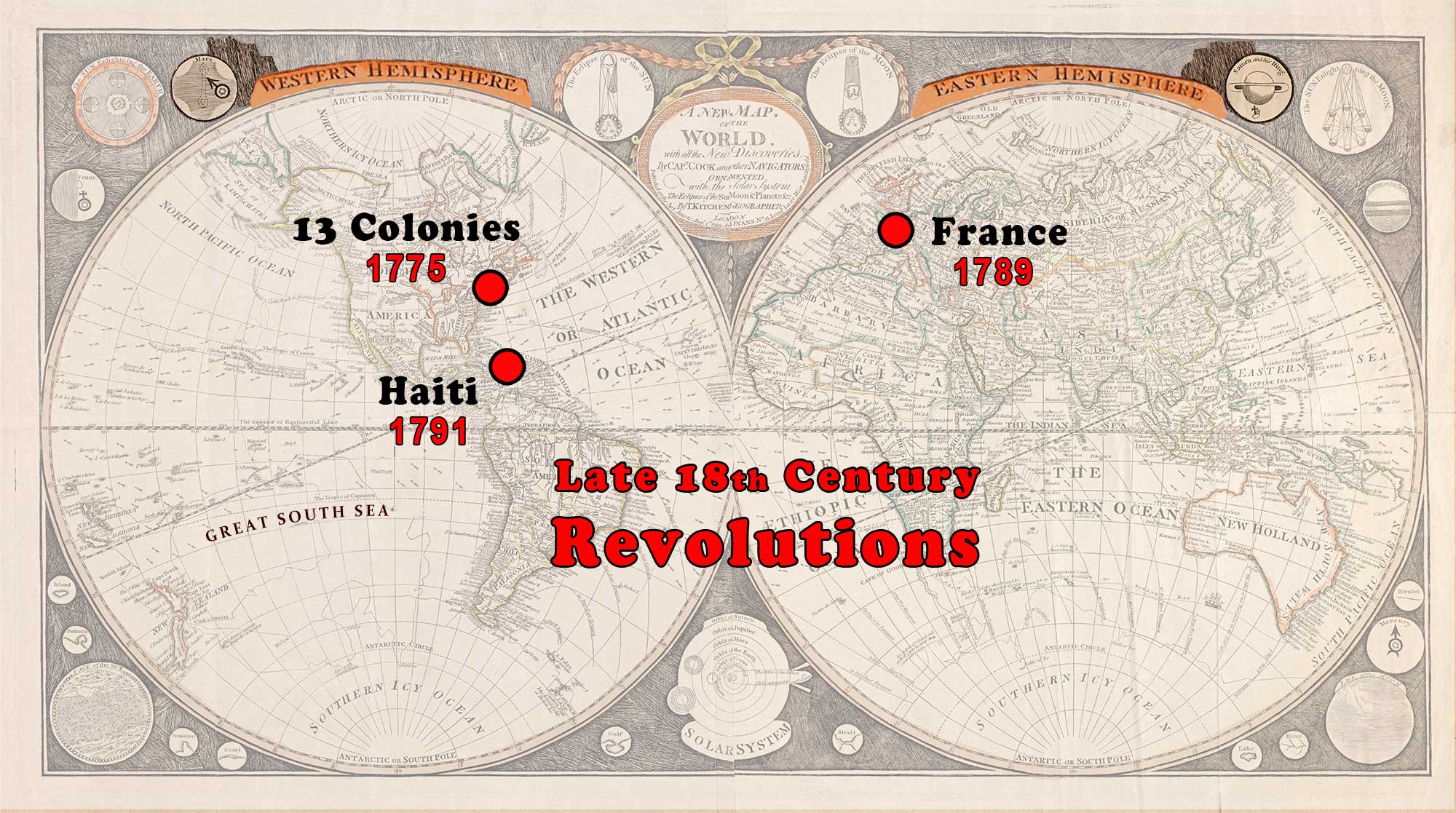

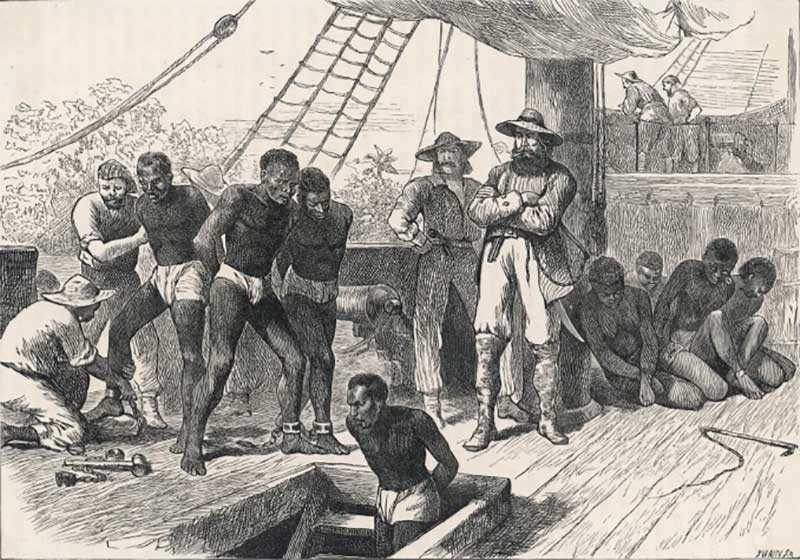

The American, French, and Haitian revolutions are commonly regarded as having moved the world away from age-old monarchy and tyranny into a brighter day of freedom and human rights. With the exception of the Haitian Revolution, though, this brighter day was forecast for some people, and not for others. Only in Haiti did human bondage cease completely.

Haitian Constitution of 1805:

“Slavery is forever abolished.”

In the summer of 1791, the enslaved Africans on the Caribbean island that we know today as “Haiti” began a guerilla war against the French army (the most powerful military force in the world, at that time). Thirteen years later, in 1804, Napoleon’s troops admitted defeat, and the first Black independent state in the Global North was born.

The 1775 rebellion by the 13 colonies against British rule, on the other hand, did not do away with slavery. The Declaration of Independence proclaimed that “all men are created equal,” with a fundamental right to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” But as it turns out, the American revolution may have given even more political power to the colonies’ slave-owning class, who no longer had to fear that Great Britain might legislate against their “property rights.” That class succeeded in writing provisions protective of the slave system into the United States Constitution. Native Americans, too, had less to fear from the British than from the colonial revolutionaries who, in the Declaration of Independence, attacked King George for giving support to “merciless Indian Savages.”

Washington reviewing his troops at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777-1778 (William Trego)

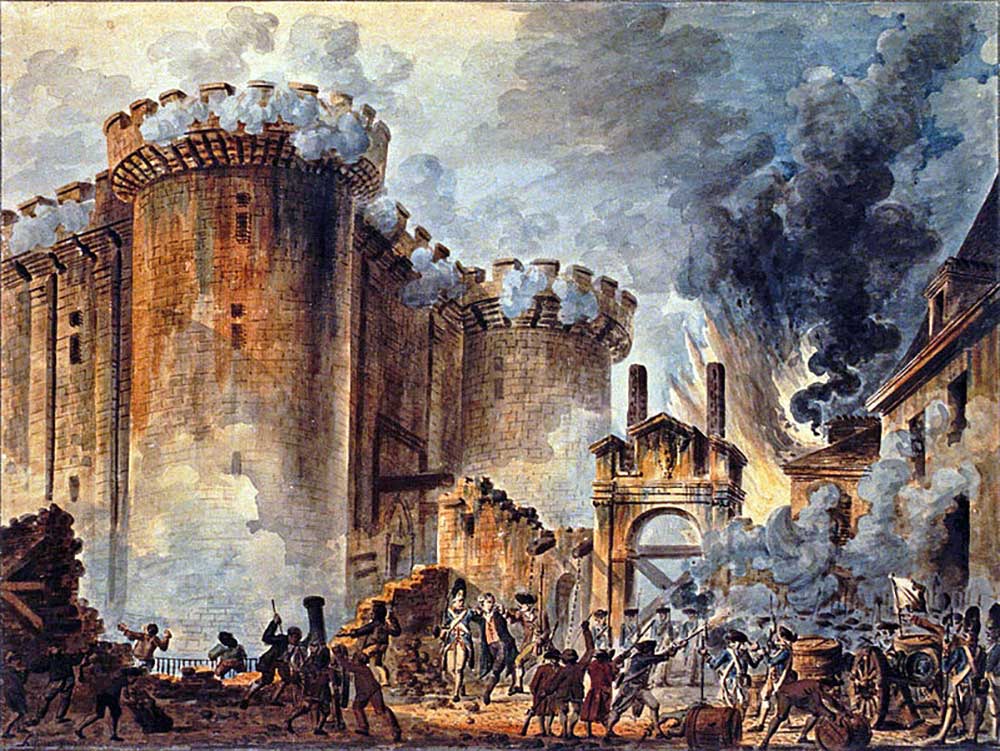

The French Revolution was hardly more exemplary. The National Constituent Assembly issued a “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” and adopted universal male suffrage briefly in 1792, but the revolution culminated in a “reign of terror” that executed more than 40 thousand “enemies of the revolution.”

The storming and burning of the Bastille prison on July 14, 1789 (Jean-Pierre Houël)

Capital Execution (Pierre-Antoine Demachy)

This was the historical context for the revolution in Haiti that began in August of 1791. Blacks on the island were aware of what was happening in France. (In the play Betrayal in Haiti, Toni comments on the fall of the Bastille.) What distinguished their revolt from others, though, was that the call for freedom was universal. Henceforth no human being, irrespective of origin, class, or race, would be in bondage.

This revolution challenged the assumption, taken for granted in Europe and its colonial empire for centuries, that the ideals of the European Enlightenment — freedom of speech and assembly, equality of human rights — were not applicable to people of color.

Across color lines existing at the time — separating Black, mixed race, and white inhabitants of the island — distrust and hatreds were intense, to be sure. Quite often, though, people whose origins were mixed race or white, even former slave owners, were welcomed into the revolutionary movement.

From the Haitian Revolution to the United Nations “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” in 1948

Many religious traditions speak of the intrinsic value of every human life. Hebrew scripture counsels, “Do not ill-treat a stranger or oppress him, for you were strangers in Egypt.” There is similar universal respect expressed in Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, and other religions.

This principle has historically not been honored by many of the world’s nations, including the United States. The American Revolution fought in the name “life, liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” did nothing to free the enslaved population living in the 13 colonies. And centuries earlier, when Europeans had first arrived on the North and South American continents, they had brutally imposed regimes of servitude upon the indigenous people they encountered.

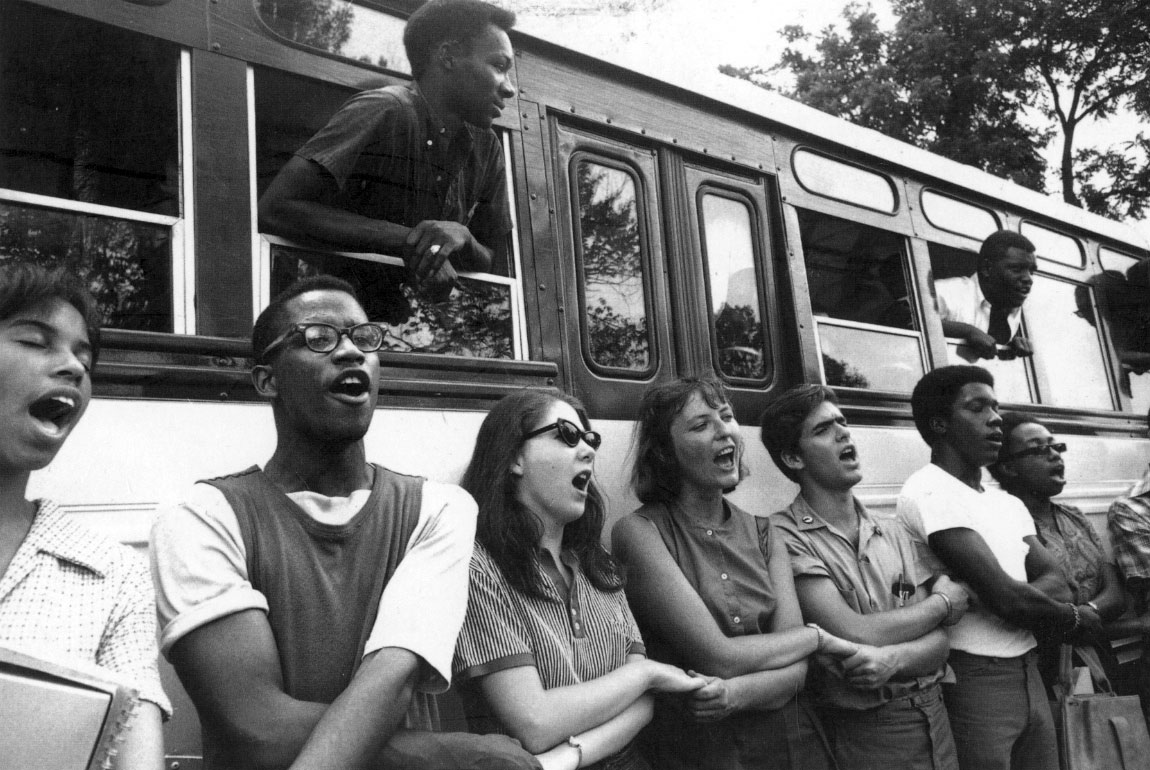

That is not the whole story, though. Parallel to the history in the “New World” of massive exploitation and violation of human rights, there has always existed a tradition of support for human equality and freedom, exemplified in the Haitian revolution over two centuries ago, in independence movements elsewhere in the Caribbean and Latin America, in the organizing by people of color in this country to achieve freedom and civil rights, and in the United Nations “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” proclaimed in 1948.

The Haitian Declaration of Independence was proclaimed on 1 January 1804, marking the end of the 13-year long Haitian Revolution.

Eleanor Roosevelt holding the U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which she helped to draft. It proclaims universal rights “without distinction of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”

Two Narratives About the Haitian Revolution

Accounts of the Haitian revolution often emphasize its violent character. Hundreds of thousands of lives were lost. But there is also a history here of peaceful coalition-building and diplomatic outreach by the revolutionaries that contributed to the success of the revolution. Toussaint Louverture and another leader, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, welcomed the support they received from free blacks and mixed race communities living in the island’s towns and cities.

Both of Toussaint’s parents had been brought to Haiti from what is today Benin, in West Africa.

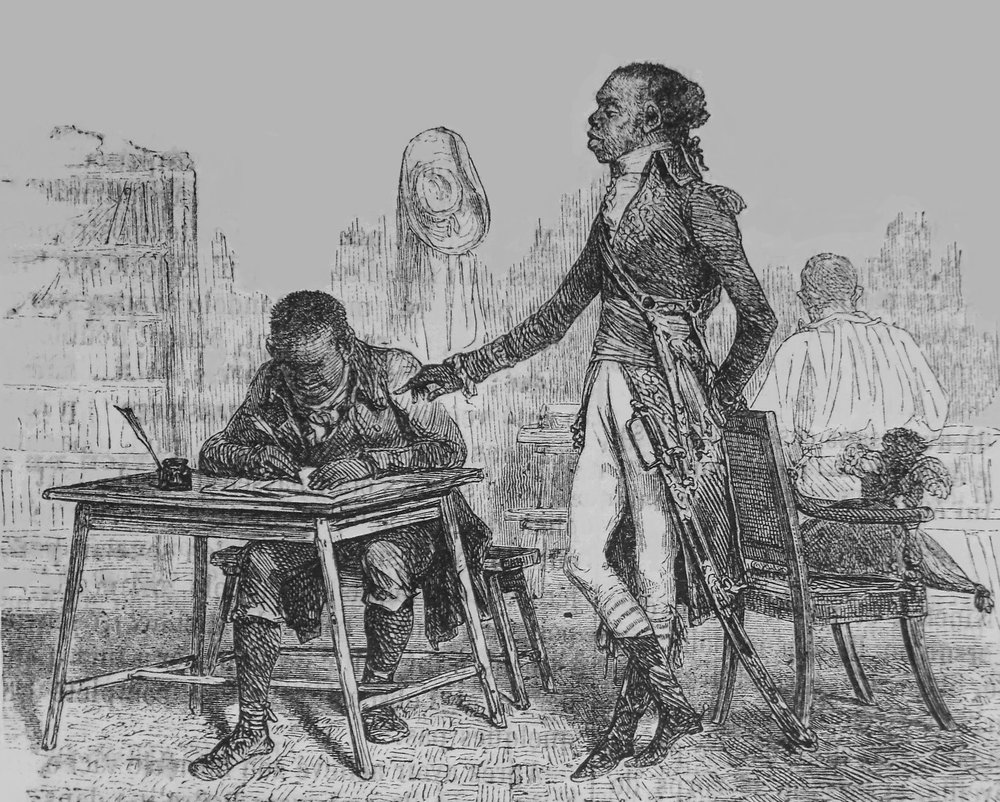

Toussaint Louverture was a battlefield general but also a skilled negotiator and law-maker.

Negotiating the withdrawal of British troops from Haiti in 1798

Welcome as well was participation on the part of whites who sympathized with the revolution and were willing to take up arms. Some white soldiers belonging to the French army switched sides and joined the revolutionary movement. French General LeClerc, who led the French military effort to restore colonial rule in Haiti, observed that upon arriving on the island, some of the troops shouted out to the rebels “that they were their brothers, their friends,” and that they had no desire to fight against them. (In the play Betrayal in Haiti, a white soldier flees from a French fort and seeks refuge on a plantation taken over by former slaves.)

Under LeClerc’s command were 4,000 men of a Polish Legion, brought into the French army through an agreement between Napoleon and a Polish general. Many of them sympathized with the slave rebellion, which reminded them of their own fight for liberty and independence in Poland. Many of them deserted the French and joined the ranks of the rebels. Some of them remained in Haiti when the colonial war ended in 1804, and their descendants still live on the island today.

Soldiers supervise a blacksmith who forges shackles to place on a woman’s wrist. She represents Poland. (Jan Matejko)

Haitian History After Winning Independence in 1804

Although French troops had been decisively defeated in the mountains, fields, and townships of Haiti, France was not about to give up its control of the island. For decades following the revolutionary war, the rulers of France continued to threaten to reconquer Haiti militarily and restore colonial rule and slavery. In 1824, King Charles X repudiated envoys that Haitian President Boyer sent to Paris to negotiate for a peaceful parting of the ways that included French recognition of Haiti’s independence as a nation.

As a condition of that independence, the king of France decreed that Haiti would have to pay 150 million francs within five years to compensate for slave owners’ lost revenue. We see below the French envoy sent by Charles X delivering the demand to Haiti’s President Boyer. To compel Haitian acceptance, this mission to the island was accompanied by 14 warships bearing more than 500 cannons.

Marlene Daut, Professor of African Diaspora Studies, at the University of Virginia, writes, “Rejection of the ordinance almost certainly meant war. This was not diplomacy. It was extortion.”

Boyer signed the document, although the amount of money France demanded just in the first installment – 50 million francs — was far more than Haiti could afford to pay. The Ordinance stated that if Haiti could not come up with this amount, it would have to borrow from a French bank. And that’s what happened; Haiti was cast deeply into debt like so many other colonized countries that have fought for and won nominal independence. Going forward from that point in time, Haiti was impoverished and unable to shape its own economic future.

Haiti was the first country in the modern world to transition from settler colonialism to imperialist domination. First France was influential, then the United States. Over the past two centuries, a similar pathway has been forced upon many other newly created nations in Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

A lesson that the world’s colonial powers learned from the Haitian Revolution:

Direct domination is not needed — Indirect works too.

- A popular revolution overthrows and expels an oppressive colonial regime.

2. That regime, exercising influence now from abroad, allies with the former colony’s business, political, and military elite to defeat progressive campaigns to build a nation state that is democratically governed, more equitable, and protects human rights.

3. Revolutionary leaders of the new nation, responding to this undermining of its independence, adopt a “fortress mentality,” enacting authoritarian measures not only to defend against foreign domination but to silence internal opposition and criticism as well.

4. Such fundamental values and aims of the revolution as equality under the law, freedom of assembly, and the right to privacy may be put on hold or even renounced. This has happened in Haiti, although protest against dictatorship has never ceased.

The Haitian Revolution was only partly successful. Although it did away with the institution of slavery, it could not guarantee that Haiti’s history following the revolution would be peaceful, democratic, or ensure human rights and dignity. But has any nation on earth really lived up to these values?

Those who carried out the Haitian Revolution over two centuries ago advanced a discussion of freedom and justice whose dilemmas and insights remain relevant to social movements in the United States and worldwide.

Additional Reading.

Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution

Laurent Dubois, Haiti. Information about Haitian history is also available on other pages of this website.

Nick Nesbitt’s account of Haiti’s contribution to advocacy for universal human rights is reviewed here.

If you would like assistance in getting reading access to any of the publications listed above, contact us here.

Video:

PBS, The Haitian Revolution

Vox, Divided island: How Haiti and the Dominican Republic Became Two Worlds

PBS, Haiti and the Dominican Republic: An Island Divided