The Haitian Revolution

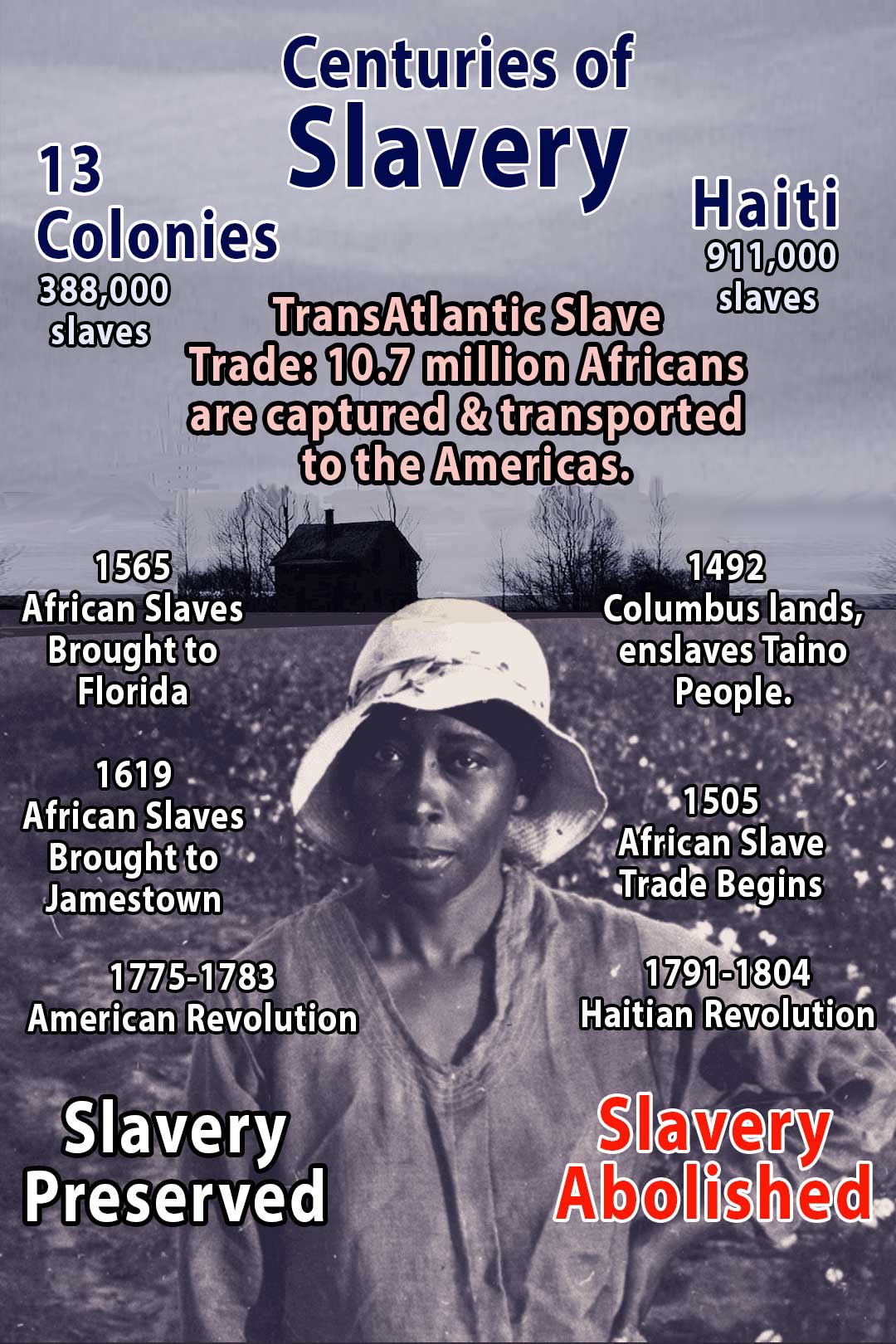

Haiti’s Constitution of 1805 states that “Slavery is forever abolished.” The historical path leading up to this declaration had been traveled for over three centuries.

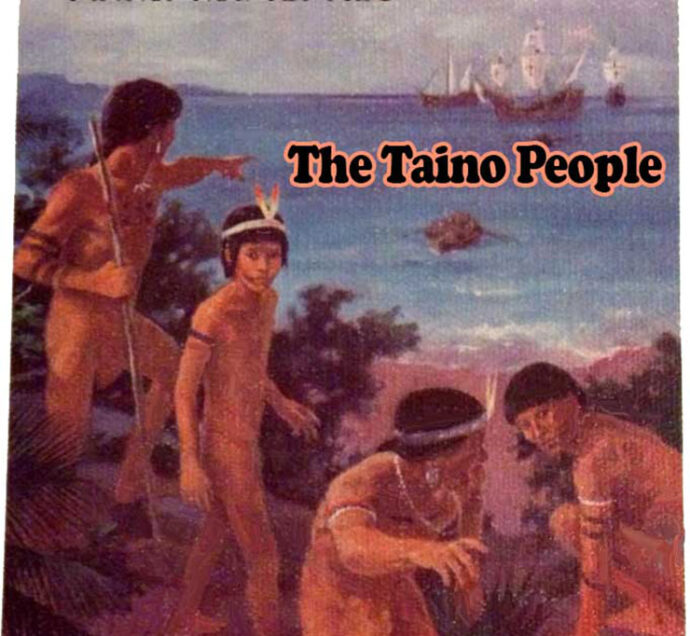

In 1492 Christopher Columbus and his crew had landed on the shore of this island in the Caribbean. Over the next several decades, the Spanish colonists, intent on profiting from their “discovery” of “the New World,” invaded the villages of the native Taino population, terrorizing men and women and putting them to work in gold mines and on plantations. Almost all of the Taino died, victimized also by smallpox and other European diseases. To replace them, the Spanish enslaved Africans and brought them to the island.

In 1492 Christopher Columbus and his crew had landed on the shore of this island in the Caribbean. Over the next several decades, the Spanish colonists, intent on profiting from their “discovery” of “the New World,” invaded the villages of the native Taino population, terrorizing men and women and putting them to work in gold mines and on plantations. Almost all of the Taino died, victimized also by smallpox and other European diseases. To replace them, the Spanish enslaved Africans and brought them to the island.

This system of exploitation, which was taken over by France near the beginning of the 18th century, was extraordinarily harsh, maintained through whipping, mutilating, hanging, and other forms of cruelty. There had always been resistance by those enslaved, but prior to 1791, the rebellions had always been brutally and successfully put down by the masters.

Then in 1789 a revolution erupted in France itself, and news reached Saint Domingue (which was the name France had given to the island) about the French “Declaration of Human Rights,” proclaiming that “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” This elevated principle was put into practice very unevenly in France and also in the newly formed United States, which would continue to support the institution of slavery until Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1862. Nevertheless, the ideals of freedom and justice voiced during the American and French Revolutions did encourage protest on the part of the white population on the Caribbean island. They resented the high tariffs imposed by France upon products purchased from abroad and other colonial policies of economic and political control.

Then in 1789 a revolution erupted in France itself, and news reached Saint Domingue (which was the name France had given to the island) about the French “Declaration of Human Rights,” proclaiming that “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” This elevated principle was put into practice very unevenly in France and also in the newly formed United States, which would continue to support the institution of slavery until Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1862. Nevertheless, the ideals of freedom and justice voiced during the American and French Revolutions did encourage protest on the part of the white population on the Caribbean island. They resented the high tariffs imposed by France upon products purchased from abroad and other colonial policies of economic and political control.

Also joining in protest against French rule were “people of color,” as the mixed-race population was called. But it was the uprising of enslaved Blacks in August 1791 that initiated the fight on the ground for emancipation.

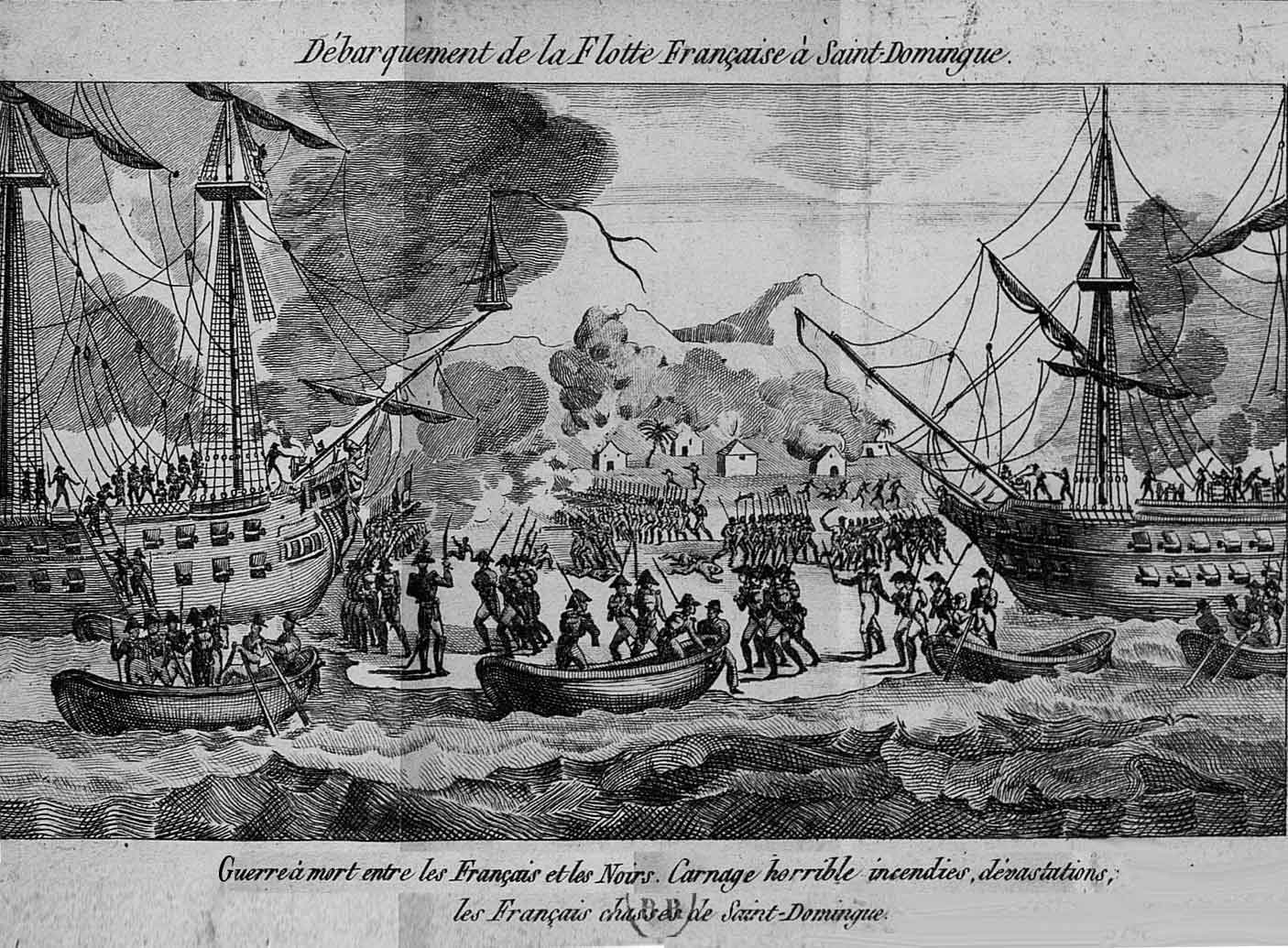

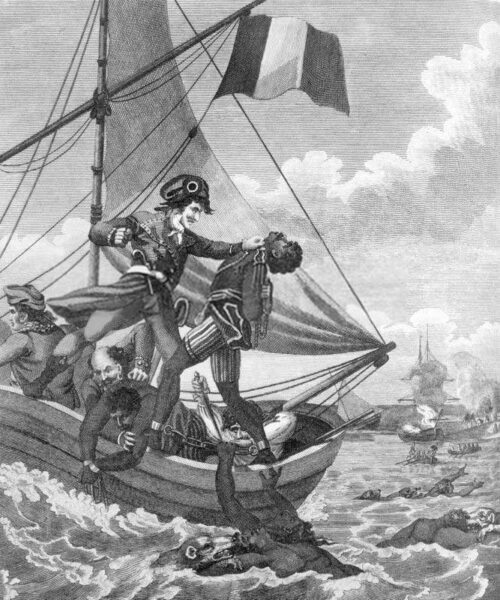

A French ship discharges soldiers on the shore of Haiti, amid “horrible carnage, fires, devastation.”

By the beginning of 1792 Black revolutionary forces had gained control of about a third of the island, and they continued to win victories thereafter. The violence wreaked by both sides was massive. During the thirteen years prior to their declaration of independence in 1804, about half of the 500,000 Blacks and 25,000 of the 40,000 whites, were killed in the fighting.

But the revolutionaries eventually prevailed, and they renamed the island “Haiti” (meaning “land of mountains” in the indigenous Taino language). Although the founders of this Black republic agreed with the declared ideals of the U.S. and French revolutions, they went beyond these models in seeking to build a nation in which every person, unconditionally and without exception, would be free.

In both the United States and France, the revolutionary slogan “All men are created equal” did not apply to those who were enslaved, to women, or to those without property. In fact slavery would not end in the United States until Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1862, long after the Haitian Constitution of 1805 had pronounced slavery dead.

The Haitian Revolution, which clearly demonstrated the ability of the Black rebels to out-think and out-organize their enemies, frightened the slave owning classes throughout the Americas, including the United States.

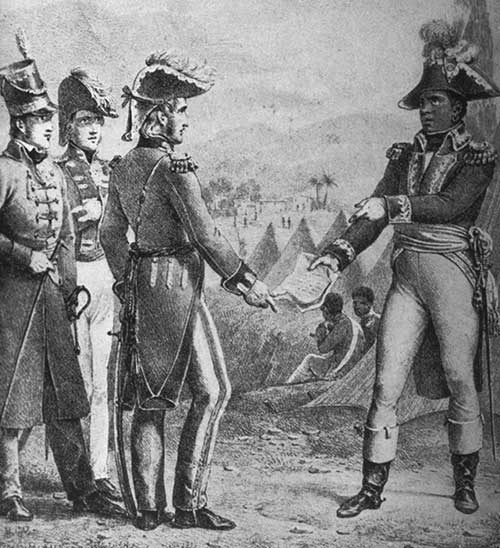

Toussant L’Ouverture, leader of the revolutionary forces, negotiating a treaty with English General Maitland in 1798. In the course of the revolution, the rebels fought not only French but also English and Spanish troops.

Burning of the town of Cap-Francais in 1793. Ships holding escaping colonial refugees desperately await permission to depart. Cap Francais was for years a battleground where rebel and French forces fought fiercely, with enormous loss of life on both sides, to control the streets and the port.

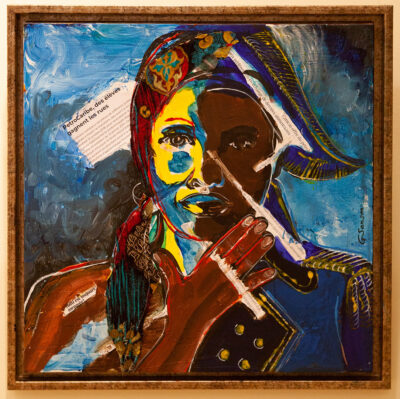

Zamba Boukman — Organizer of the Uprising in 1791

Betrayal in Haiti is a play that is anchored in the history of the Haitian Revolution, and many of its references are to particular historical circumstances and persons. The drama gets underway following the death of Zamba Boukman, who was the firebrand and inspiration for the collective uprising in 1791 by those enslaved. The first scene features a speech delivered by a revolutionary leader whose aim is to motivate his discouraged followers to persist in their fight for freedom. He reminds them of the role played by their fallen hero before the insurrection began: “Zamba Boukman. I knew him the same way you did. Secretly at night he came to our plantations and told us to throw off our chains and fight and win.”

Zamba Boukman was in fact the main organizer of the insurrection. Transported to Saint Domingue as a slave, he had escaped into the forest and became a Vodou priest. He was a brilliant, persuasive advocate, learning from the failed revolt of Francois Makandal a few decades earlier and convinced that only a well-planned and ruthless campaign could succeed in expelling Europeans from the island. He went from one plantation to another, encouraging those enslaved to get prepared for unified action. He then became a military leader of the rebellion that he had so patiently prepared, but was killed on 7 November, 1791.

The French displayed Boukman’s head in public, to prove to the rebels that, contrary to their faith in the man, he was in fact mortal, and that they too would be killed if they continued to resist. His loss was indeed a setback, but the former slaves were able to regroup and eventually to prevail. In the play, it is their fierce resolve to be free that the speech given by their leader, Congo Hoango, counts on and renews.

Literacy. Before arriving in Saint Domingue, Boukman had been owned by a British slave-master, and his name, which was derived from the English “book man,” may have been given to him because of his reputation for teaching first himself and then others to read. This was a remarkable achievement, since reading was an activity for which someone enslaved could be severely punished, even put to death.

In the play, Babekan, a former female slave, has taught herself to read and write — skills that she considers essential to a free life. She has imparted those skills to her daughter Toni too, who in turn teaches literacy to others and anticipates a future for herself as a school teacher after the revolution establishes a new nation.

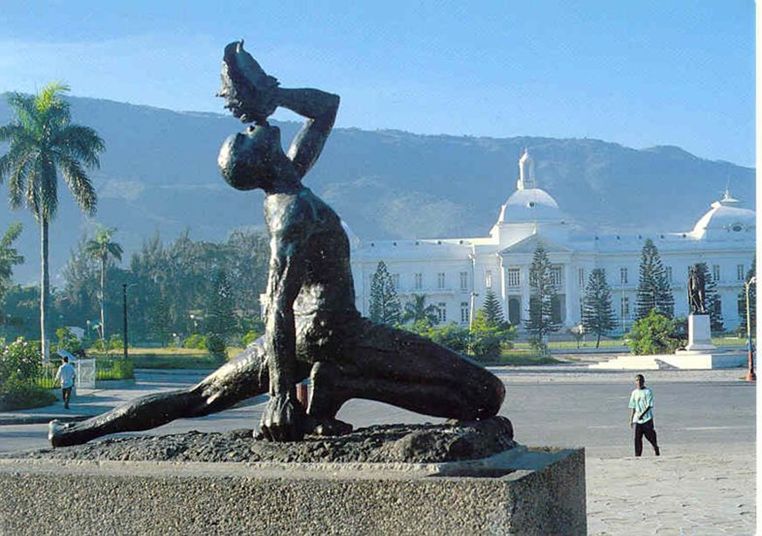

Albert Mangones, Black Maroon, Port-au-Prince

A maroon was a slave who had escaped into the forest. Many maroons, including Boukman, secretly visited plantations. Some belonged to families that were plantation slaves.

Boukman’s life has inspired many of Haiti’s community organizers. One of them even took his name. Samba Boukman was an activist working in impoverished neighborhoods in the capital city of Port-au-Prince, until his assassination in 2012.

Women in the Haitian Revolution

Upon arrival on the island of Saint Domingue, the average life expectancy of a slave was about seven years. Women suffered as much as men. Because of their sex, they were subject to additional abuse by plantation masters and overseers, including rape and other forms of sexual exploitation. They resisted in every way possible: marronage (escape to the forest), sabotage, abortion, poisoning their masters, infanticide, and other forms of non-cooperation, including suicide.

And when the insurrection got underway, women participated at every level. When a plantation was taken over by its former slaves, women help to re-organize life within them, as is the case in the play Betrayal in Haiti: Babekan is in charge of the plantation that is the setting for this drama.

Women also provided food and supplies to the soldiers and nursed them when they were wounded. They themselves took up arms to help defeat the white troops. There had been in West Africa a long tradition of women warriors fighting alongside men in battle. Black women in Saint Domingue continued this practice.

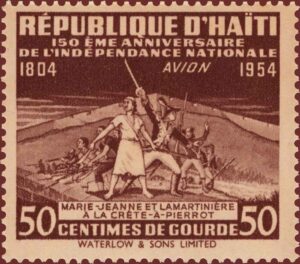

Marie-Jeanne Lamartinière was a leader in the battle at Crête-à-Pierrot.

Lieutenant Sanité Bélair (1781-1802)

Gina Samson, Sous le regard des Ancêtres (Under the Gaze of the Ancestors), 2018

There is a saying in Creole: “Fanm se poto mitan,” meaning that women are the pillars of society.

Faithful Ally to the Uprising: Yellow Fever

Infectious diseases such as malaria, smallpox, and yellow fever have undermined countless military campaigns in the past. In the case of the Haitian revolution, it was yellow fever that ravaged the occupying troops and contributed to the success of the slave revolt. When Congo Hoango says in the play Betrayal in Haiti, “An avenging god is sweeping through the ranks of the white soldiers,“ he is referring to this disease. From the beginning of the revolution in 1791 until the final defeat of European forces in 1803, yellow fever assaulted the white invaders. Although those who were enslaved died from the disease too, they had gained some herd immunity because of their lifelong exposure.

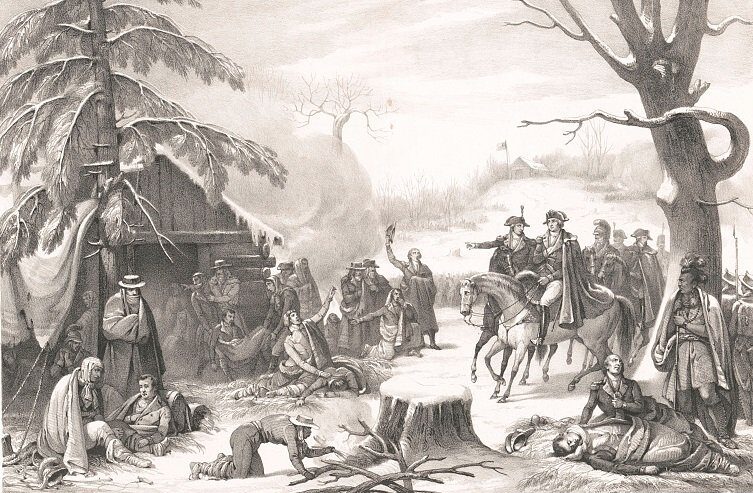

In North America during the revolution that preceded the uprising in Haiti by about 16 years, smallpox afflicted George Washington’s Continental Army and British troops also. Despite this illness, the revolutionary forces prevailed and succeeded in establishing a new nation.

Accompanied by Lafayette, George Washington visits the troops at Valley Forge, diseased and dying from smallpox.

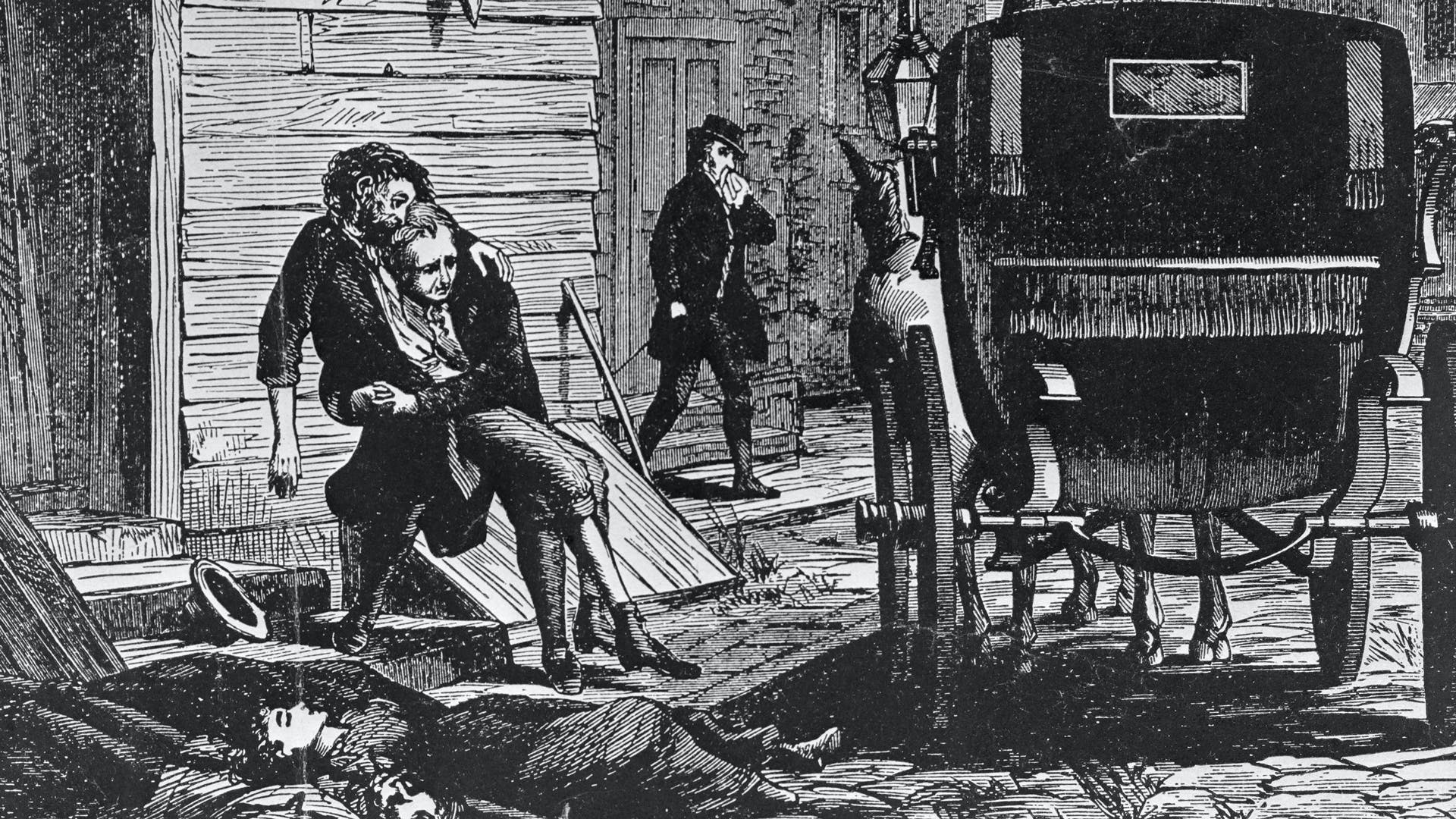

Thousands of colonial families fled Saint Domingue during the years of the revolution, seeking to escape not only the insurrection itself but also disease. But many of them were already infected. In the summer of 1793 Philadelphia was struck by a yellow fever epidemic that was probably brought to the city by these refugees. As many as 5,000 Philadelphians died from the virus (10% of the population). About 17,000 residents left the city to escape the disease. Philadelphia was the capital of the U.S. at the time, and among those leaving were Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and many Congressional representatives.

In 1802, the leader of the French army, General Charles Leclerc, reported that he had lost one-third of his soldiers to yellow fever. Leclerc died from the disease himself and was replaced by General Rochambeau, who deployed every available means to smash the insurrection. Black civilians and combatants alike were executed in large numbers by burning and drowning. Some were eaten alive by hundreds of attack dogs that had been brought to Saint Domingue from Cuba. Nevertheless, yellow fever continued to demolish the French ranks. When the disease had killed more than 20,000 additional soldiers shipped to the island by Napoleon, and Rochambeau had lost the Battle of Vertières, he agreed to a cease fire with the Haitian leader Dessalines. It was made clear to the administrative authorities in Paris that their forces could not win the war, and the remaining French troops, acknowledging final defeat, left the island at the end of November, 1803.

The loss of France’s most profitable colony led Napoleon and his advisors to re-evaluate the benefits and costs of holding on to French-claimed land in North American. Learning from the defeat in Saint Domingue, France sold the Louisiana Territory to the United States in 1803, thereby nearly doubling the size of the country.

To learn more about what happened during and after the Haitian Revolution, visit other pages of this website. Additional sources of information are listed below.

Engraving from Rainsford’s An Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti (1805). Marcus Rainsford was a British military officer who observed first-hand the cruelties inflicted by General Rochambeau, depicted here as a boat captain.

Additional Reading

Bryan Stevenson, “Why American Prisons Owe Their Cruelty to Slavery”

Nicole-Hannah Jones, The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution

Caroline Orange, “Yellow Fever Was Just As Important as Toussaint L’Ouverture in the Haitian Revolution”

Laurent Dubois, Haiti

C.L.R. James, Black Jacobins

Other excellent historians of Haiti include Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Carolyn Fick, David Patrick Geggus, and Jeremy Popkin.

If you would like assistance in getting reading access to any of the publications listed above, contact us here.

Video:

PBS, The Haitian Revolution

Vox, Divided island: How Haiti and the Dominican Republic Became Two Worlds

PBS, Haiti and the Dominican Republic: An Island Divided

History of Haiti 5000BC – 2021