Black Soul (1947)

by Jean-Fernand Brierre

I have met you in the elevators

in Paris.

You would say you were from Senegal or the Antilles.

And the oceans you had crossed would foam at your teeth,

haunt your smile,

sing in your voice as in the hollows of the rocks.

In the broad daylight of the Champs-Elysees

I would suddenly pass your tragic faces,

and your masks would speak out their centuries of pain.

At the Boule-Blanche

or in the bright lights of Montmartre

your voice,

your breath,

your whole being oozed joy.

You were music and you were dancing,

but at the corners of your lips remained,

uncoiling with the movements of your body,

the black serpent of misery.

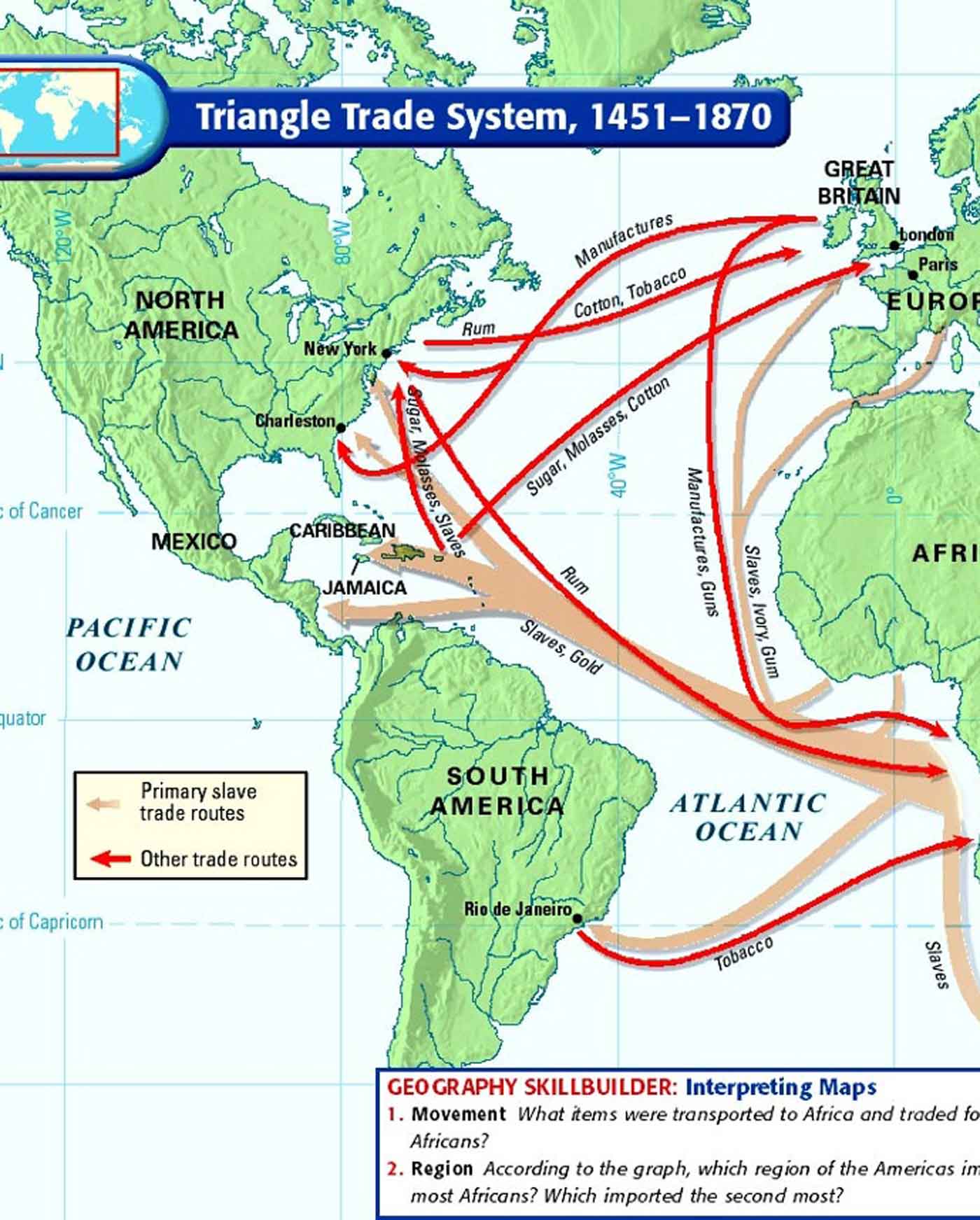

We have spoken to one another aboard ocean liners.

You knew the brothels all over the world

and how to make love in every language.

Every race had fainted away

under the strength of your embrace.

And if you didn’t shrink from opium or cocaine

it was only to try to put to sleep

in the depth of your flesh the bite of the whip,

the humbling gesture that cracks the knee

and, in your heart,

the dizziness of silent suffering.

You would come from the galley

and toss a loud rippling laugh at the sea

like an offering of pearls.

But when the liner shook

with opulent laughter and luxurious joy,

your shoulders still bent with the burden of the day,

somewhere back in a corner you sang for yourself alone,

to the sad twang of the banjo’s lament,

the music of loneliness and love.

You built oases

in the smoke of a filthy cigarette

that tasted like a clump of Cuban dirt.

In the night sky you would show the way

to a seagull lost and chilled

in the thickening fog

and you would listen, tears in eyes,

to its last sad farewill

from the shadow’s edge.

Sometimes you would stand at the prow, bronze god,

moon-mist shining in the diamonds of your eyes

and your dreams would come to rest in the stars.

Five centuries have seen you with weapons in hand

and you have taught the races that exploited you

the passion for liberty.

At Santo Domingo

you staked out with suicides

and paved with nameless stones

the tortuous path that opened out one morning

onto the triumphant road of independence.

And you have held above the baptismal font–

grasping in one hand the torch of Vertieres

and with the other shattering the chains of slavery–

the birth of Liberty

for all of Spanish America.

You built Chicago

while singing the blues,

built the United States

to the rhythm of your spirituals,

and your blood ferments

in the red furrows of the star-spangled banner.

Out of the darkness

you leap into the ring:

champion of the world,

and with each victory you sound

the deep-voiced gong that sings the claims of your race.

In the Congo,

in Guinea,

you pitted yourself against imperialism,

fighting it

with drums,

with strange melodies

moaning out in wave upon wave

the chorus of your centuries of hate.

You lit the world

with the light of your fires.

In the dark days of a martyred Ethiopia,

you ran from every corner of the globe,

chewing out the same bitter notes,

the same fury,

the same cries.

In France,

in Belgium,

in Italy,

in Greece,

you stood up to danger and death. . .

And on the day of triumph,

after the American soldiers had chased you

out of a Paris cafe

with Rene Maran,

you were sent back

in boats

where they already rationed out your space

pushing you back to the galley,

to your tools,

your broom,

your bitterness,

in Paris,

in New York,

in Algiers,

in Texas,

pushing you behind the savage barbed-wire fences

of the Mason Dixon Line

of every country in the world.

Everywhere they stripped you of your weapons.

But can they strip the weapons from a black man’s heart?

If you have laid aside the uniform of war,

you have not given up your countless wounds,

and their closed lips still speak to you in a low whisper.

You are waiting for the next call,

the inevitable call to arms.

Your war knows none but a temporary truce,

for there is no land where your blood has not been shed,

no tongue in which your color has not been cursed.

You smile, Black Boy,

you sing,

you dance,

you rock the cradle of the generations

that are still coming, that keep coming

onto the battlefields of work and suffering,

that will be coming tomorrow to lay siege to the bastilles

and bastions of the future

to write in every tongue,

on the bright pages of every sky,

the declaration of your rights,

ignored for five long centuries and more,

in Guinea,

in Morocco,

in the Congo,

and wherever your black hands

have left on the walls of Civilization

their prints of love, of beauty and of light.

Source: N. Shapiro (ed.) Negritude: Black Poetry from Africa and the Caribbean. New York (1970)